You can follow the link below to see the answer.

Meanwhile you can if you like take a look at this PDF document on “What we wish people knew …”

And now for that link mentioned in the first sentence of this post:

!? Timothy Morton:“flushable”: just because you can doesn’t mean you should

— George Atherton (@notrehta) October 7, 2019

the NYT ran this: https://t.co/Icye7xdHe4https://t.co/jvtqJH7yol

When we flush the toilet, we imagine that the U-bend takes the waste away into some ontologically alien realm. Ecology is now beginning to tell us of something very different: a flattened world without ontological U-bends. A world in which there is no “away.” Marx was partly wrong, then, when in The Communist Manifesto he claimed that in capitalism all that is solid melts into air. He didn’t see how a kind of hypersolidity oozes back into the emptied out space of capitalism, a hypersolidity I call here hyperobjects. This oozing real comes back and can no longer be ignored, so that even when the spill is supposedly “gone and forgotten,” there, look! There it is, mile upon mile of strands of oil just below the surface, square mile upon square mile of ooze floating at the bottom of the ocean. The cosmic U-bend is no more. It can’t be gone and forgotten – even ABC News knows that now.

When I hear the word “sustainability” I reach for my sunscreen.

source: Adbusters article (Jan/Feb 2012) – saved on archive.org

Tim Morton: Peak Nature | Adbusters Culturejammer Headquarters - An amazing essay by Tim Morton - I... http://t.co/M3smY57z

— Joe Flintham (@joeflintham) January 21, 2012

“An amazing essay by Tim Morton – I recommend listening to George Atherton’s reading for the full weight of oozing of spilt oil and worlds that don’t exist.” —Joe Flintham

* * *

partial transcript, a copy-paste:

Common knowledge presumes that we have a choice between fossil fuels and green energy, but alternative energy technologies rely on fossil fuels through every stage of their life cycle. Most importantly, alternative energy financing relies ultimately on the kind of economic growth that fossil fuels provide. Alternative energy technologies rely on fossil fuels for raw material extraction, for fabrication, for installation and maintenance, for back-up, as well as decommissioning and disposal. And at this point, there’s even a larger question: where will we get the energy to build the next generation of wind power and solar cells? Wind is renewable, but turbines are not. Alternative energy technologies rely on fossil fuels and are, in essence, a product of fossil fuels. They thrive within economic systems that are themselves reliant on fossil fuels.

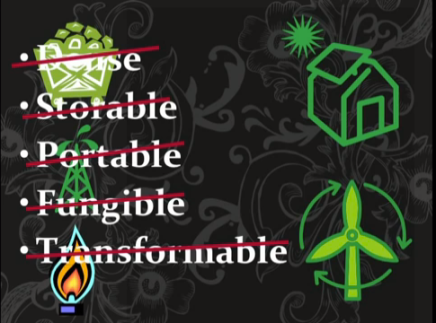

Now, I’m no fan of fossil fuels. Fossil fuels are finite and dirty, but we use them for five principal reasons. Fossil fuels are dense. Their energy is storable, portable, fungible (which means they can be easily traded), and they are transformable into other products like pesticides, fertilizers, and plastics.

Now, these qualities cannot be measured in kilowatts, so what happens when we spend our precious fossil fuels on building alternative energy. Well then we get energy that is not dense, but diffuse. It’s not easily storable. It’s not portable. It’s not fungible. And it is non-transformable.

Now to increase the quality of the energy, we then have to spend more fossil fuels to build batteries, to build back-up power plants, and other infrastructure. And of course this is incredibly expensive. Ultimately that expense represents the hidden fossil fuels behind the scene.

There’s an impression that clean energy can supply a growing population of high consumers. There’s an impression that alternative energy can displace fossil fuel use, but the evidence doesn’t show that.

A Perfect Spy (p. 168)

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from My Life (preface)

How could anyone diaeresist!

— Katherine Semel (@ksemel) October 31, 2019

Requirements:

- two years’ experience as a copy editor

- a flair for writing display copy that engages the reader and adheres to The New Yorker’s voice and outlook

- experience and comfort with digital publishing and an ability to work both quickly and accurately

- a strong interest in current affairs and culture

- the ability to meet deadlines while handling multiple tasks simultaneously

- the ability to work both independently and as part of a team

- the ability to communicate and coördinate with editors, writers, fact checkers, and others, balancing needs and priorities while upholding copy standards

- familiarity with the history, style, and values of The New Yorker

The four stages of acceptance:

— George Atherton (@notrehta) September 1, 2018

1) This is worthless nonsense

2) This is an interesting, but perverse, point of view

3) This is true, but quite unimportant

4) I always said so

—J.B.S. Haldane (Journal of Genetics 1963, Vol. 58, p.464) https://t.co/pzDLqpisB6 via @goodreads pic.twitter.com/uuljs3rz6W

J. B. S. Haldane, in full John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (born Nov. 5, 1892, Oxford, Oxfordshire, Eng.—died Dec. 1, 1964, Bhubaneswar, India), British geneticist, biometrician, physiologist, and popularizer of science who opened new paths of research in population genetics and evolution.

Son of the noted physiologist John Scott Haldane, he began studying science as assistant to his father at the age of eight and later received formal education in the classics at Eton College and at New College, Oxford (M.A., 1914). After World War I he served as a fellow of New College and then taught at the University of Cambridge (1922–32), the University of California, Berkeley (1932), and the University of London (1933–57).

In the 1930s Haldane became a Marxist. He joined the British Communist Party and assumed editorship of the party’s London paper, the Daily Worker. Later, he became disillusioned with the official party line and with the rise of the controversial Soviet biologist Trofim D. Lysenko. In 1957 Haldane moved to India, where he took citizenship and headed the government Genetics and Biometry Laboratory in Orissa.

Haldane, R.A. Fisher, and Sewall Wright, in separate mathematical arguments based on analyses of mutation rates, population size, patterns of reproduction, and other factors, related Darwinian evolutionary theory and Gregor Mendel’s concepts of heredity. Haldane also contributed to the theory of enzyme action and to studies in human physiology. He possessed a combination of analytic powers, literary abilities, a wide range of knowledge, and a force of personality that produced numerous discoveries in several scientific fields and proved stimulating to an entire generation of research workers.

Now, my own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose. I have read and heard many attempts at a systematic account of it, from materialism and theosophy to the Christian system or that of Kant, and I have always felt that they were much too simple. I suspect that there are more things in heaven and earth that are dreamed of, or can be dreamed of, in any philosophy. That is the reason why I have no philosophy myself, and must be my excuse for dreaming.

― J. B. S. Haldane, Possible Worlds